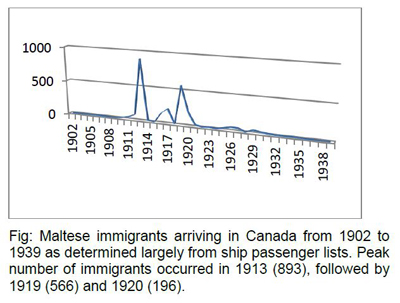

Distribution of Maltese in Canada before WWIIThe Distribution of the Maltese in Canada up to the Eve of the Second World War By Dan Brock* Only fragmentary data are available relating to the numbers and distribution of the Maltese in Canada. There are the decennial censuses which begin with that for 1851. While there are the printed abstracts, only the manuscript copies for the years up to and including 1921 are presently available to the public. We have annual lists of immigrants to Canada in the Canada Year Book, but they only start in 1913 and don't appear to consider those who came via an American port such as New York. Meanwhile, the late Fr. Lawrence Attard had done sterling work relating to Maltese migration to Canada in such publications as: Early Maltese Emigration (1900-1914) (1983), The Great Exodus (1918-1939) (1989) and The Safety Valve (A History of Maltese Emigration from 1946) (1997). More recently, Mark Caruana in Australia has done extensive studies collecting data relating to Maltese migration based on information obtained from the examination of ship lists at the point of disembarkation and passports issued in Malta. These have given us further information about the movements of Maltese emigrants. I have followed in the footsteps of these researchers, in this case, to attempt to clarify further the main distribution of Maltese immigrants in various localities in Canada from the early stages of migration up to the eve of the Second World War. Based largely on the censuses up to and including 1901, I have determined that there were less than 100 individuals of Maltese birth or blood who had immigrated to present-day Canada by the end of the nineteenth century, beginning with Louis Shickluna (Scicluna) in 1826. Moreover, some two-thirds of these were "Maltese" by accident of birth as both parents were non-Maltese, as determined by the fact that their place of birth was not Malta, their surnames were not Maltese, the stated religion was mainly Protestant and the fathers were, with few exceptions, in the British Army. These then were children born of families connected with the British Armed Forces stationed in Malta at the time. Of the less than 30 persons of Maltese blood, more than one-third were living in the Niagara Peninsula where Louis Shickluna had his Great Lakes shipbuilding operations in St. Catharines and his nephew Salvu Shickluna (Scicluna) operated the shipyard at Port Colborne. Both appear to have employed a handful of workers directly from Malta. The figures are even worse in the 1911 census for those born in Malta and of Maltese blood. Based on Ancestry online, of 113 who were enumerated as born in Malta, only about five could be said to have been of Maltese blood, the rest being mainly Protestant, of parents born in England, Scotland or Ireland. One of the five Maltese immigrants was Vincenzo Mifsud of Vancouver, British Columbia who, in December 1981, celebrated his 100th birthday! Now, if we look only at the known destinations found on the ship lists at the point of disembarkation, both in Canada and in the United States, as compiled by Mark Caruana in 2009, further supplementing these with additional data by myself and excluding those who were visitors, returning immigrants, deportees and stowaways, it would appear that, by the end of 1912, Winnipeg, Manitoba had the largest Maltese-born population, with a little more than 30, followed by Toronto, Ontario, less than 30, Montreal, Quebec, about 25 and Calgary, Alberta, less than 20. But, while the relative proportions might be fairly accurate, the numbers of actual Maltese residents in these communities is most likely exaggerated. These numbers don't allow for those who returned to Malta, moved elsewhere within Canada, migrated to the United States or Australia or simply died. On the other hand, it is known that there were Maltese immigrants, such as stowaways or crew members on merchant vessels, coming into Canada during these years for whom we simply don't have any documentation. These may have augmented the numbers in the communities selected. Be this as it may, the accompanying graph shows arrivals based on what Mark Caruana has extracted from ship lists, supplemented by my ongoing research. It can be seen that very few Maltese migrants arrived in Canada from 1902 to 1912 (153). There was, however, a significant increase in 1913 (893). This was a number greater than the total of all arrivals from Malta up to that date. Moreover, this number was not exceeded in a subsequent year until 1951. Numbers dropped to very low levels during the first two years of the First World War (22), but increased again considerably over the 1916-1917 period (358). In the following years, the annual number of migrants was significantly less. The total number of documented migrants arriving in Canada over the whole period from 1902 to 1939 was 2,499. Based largely on the destinations given by the ship lists, from 1902 to the end of 1913 it would appear that over 500 Maltese had given their destination as Toronto. Montreal was the second choice with about 200, followed by Winnipeg with over 100, Brantford, Ontario with over 85 and Victoria, British Columbia with about 60. As noted above, however, many of these individuals were on the move, finding better sources of employment, etc. and, while the rankings of the various cities may very well be indicative of the main centres of Maltese population in Canada in 1913, the numbers of actual Maltese residents would be assumed to be lower than the original city of destination would indicate. As a case in point, in 1916, the Capuchin priest, Father Fortunatus Mizzi of Valletta, paid a visit to the Maltese in Toronto. On July 5, 1916, he wrote that they numbered only some 200 people, consisting of 14 families with 27 children. Apart from the children and 15 women in all, the rest were men. Some of these were expecting the arrival of their wives and children; others had arranged for their Maltese brides to join them. Another reason at this time for the difference between Father Fortunatus' estimate and the numbers who were destined for Toronto up to this date is that after the outbreak of the First World War many of the men had either returned to Malta to take up arms in the British armed forces, or had joined the Canadian armed forces by this time. Using Father Fortunatus' figure as the benchmark, however, and comparing this with the ship list data up to the end of June 1916, I believe it fairly safe to say that, after Toronto, Montreal was the most populous Maltese community in Canada with a population of about 80 Maltese immigrants. This was followed by Winnipeg (c. 40), Brantford (c. 35), Victoria (c. 25) and Calgary, Alberta (c. 10). Maltese immigration to Canada fluctuated from year to year during the remainder of the 1910s. Another high of over 550 was reached in 1919 dipping to under 200 the following year. Now if we study the 1921 Canada census, the last one to be made available to the public, we see that of the 832 enumerated individuals who listed Malta as their place of birth, 481 were living in what is now the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). This was followed by 45 in Montreal, 40 in Brantford and 23 each in Winnipeg and in Vancouver. Calgary had 10 and Victoria seven. Thus, given the shifting of the Maltese population from coast to coast, it would appear that the rankings and approximations for the year 1916 are not all that out of line. After 1920, the numbers Maltese immigrating to Canada dropped to double digits, then single digits and, in the case of 1938, none at all. Now, while I have calculated the destination of over 1,500 of those who arrived between 1902 and 1939 to be Toronto, Fr. Attard's statement that "Toronto's Maltese population in 1939 barely reached the one thousand mark..." seems quite plausible, based on what we have seen up to this point. I again believe I'm on safe ground when I state that Montreal still had the second largest Maltese population in Canada. When compared to Toronto, Montreal's would probably have been about 165. This was followed by Brantford (c. 100), Winnipeg (c. 85), Victoria (c. 40) and Calgary (c. 30). Vancouver's Maltese population in 1939 would have been about 15 and Windsor, Ontario's would have been about 10. As for London, Ontario, its Maltese population on the eve of the Second World War was virtually nil. It is only after the March 1, 1948 agreement, reached between Malta and Canada to allow 500 men from Malta, and subsequently their families, to migrate to Canada, that the London area became a destination. While we don't have recent census data on those born in Malta, if we use the 2011 Canadian census, and the number who claimed Maltese as their mother tongue, we can provide another gauge by which to determine the relative distribution of the Maltese in the major centres. The Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) of Toronto listed 4,020, followed by the London CMA (including St. Thomas) of 290, Oshawa, Ontario (280), Windsor (225), Hamilton, Ontario (190), Vancouver (85), Guelph, Ontario (75) and Brantford (60). Moreover, places like Oshawa, Hamilton, Guelph and even Brantford can be considered today as bedroom communities for the GTA. While the actual number of those of Maltese blood today would be several times more than the above figures, we can still say that, in contrast with the situation in 1939, London's Maltese population is second, albeit a far distant second, only to that of the GTA. Moreover, London is one of the very few communities outside the GTA to have a Maltese club or association and it is the only one to have its own building.

* I wish to thank Prof. Maurice Cauchi of Australia for his comments and assistance in the preparation of this article. [Published in The Maltese Canadian Club of London Newsletter Vol 38 No. 2, July/August 2017]

|

![]() .

.